THE SHIFT: A conversation with Olivia Olsen

Olivia Olsen, recent contributor to THE SHIFT, is a playwright, actor, and storyteller with a background that also includes dance. She teaches extensively and performs. Wild Dogs, her play about the poet Anna Akhmatova premiered in 2019 in London and she is currently writing a new work.

Olivia talks with Susan McKenzie.

SM

The Shift Series looks at somatic practice in art. What does “somatic” mean to you?

OO

I don't actually use the word somatic. But I can share what interests me.

Olivia Olsen

My best acting moments come when there is no division between thought, emotion, image, physical sensation and action. The same happens in a good decision, hearing a poem, a focused act, a new idea, a joke. No separation between intention, mind, feeling and body. How different aspects of our humaness are connected, how they interpenetrate, how they cause and effect each other… that, for me, is an unfolding interest.

I experience my body as a changing yet organized being. It has variation of substance, different qualities of energy, shapes and movements, and senses including sense of balance, sense of truth, sense of the other. I experience a small potential of all my body is, and could do. My soul interpenetrates my body - another person’s soul would notice and use this body differently, make other choices, develop different responses. Over time, their soul would change my body; maybe it would run faster, different thoughts, which would change reflexes and health, gestures, how the senses engage etc.

And then there is the world beyond my skin, also physical, emotional, mental and life forces passing through, all affecting my self in this body. There is interchange and conversation between my embodied self and the world/other. We resonate and respond to each other.

For me, art is a measured choice, to reveal through one or more senses a part of the All. Make that something conscious…. a lamp, illuminating a specific ‘This’.

“Somatic” may be an aspect of the whole you could choose to focus awareness on. I do not separate it from other functions of my self. This is an experience I had. I was in Yorkshire on the moors. A bright day, old flowing mountains, heather, grasses, bushes, ravines with streams. Big sky. I was learning a new script for a show and often do it walking. I sat, back to a slope looking to a gully speaking out loud. As I did I found that the landscape around me wasn’t as separate a being from my body as I normally judge it to be. Because I walk though and pass by, I have separated its substance from my own, its’ life from my own, its’ consciousness from my own. But not now. The moor was my body as much as my bones and flesh. When I said words, the earth resonated with me. The hill carried the feeling and thought and was a container and transmitter for language in the same way as my own ribcage or throat. When I focused on blades of grass, bits of blossom, on the water, and every separate part of what was around me, the story was embodied in that as well as my own body. This enlargement of ‘body’ engendered expression more wonderful than I have ever known. This was not an out-of-body experience, trance. It was: ‘my body and nature are united, and my consciousness can behold itself in any part of that.’ So I told the story through my legs, the gorse bush, the rusty stream, my hips, the pine behind.

It seems to me from the moor that it is possible to blend with or inhabit any part of what is around us, and live creatively with it as an extended body. There is sensation of life in my skin and outside my skin - and this includes language and speech. Speech sounds are not separate from rocks and breezes and spiky grass. I believe the human voice resonates them and they resonate us. Language doesn’t just describe the natural world like a sign. I believe words and patterns of words are the natural world in a sound form. Probably the Bards of Ireland and Ancient Greece, Sanscrit, and the Indigenous voices of Turtle Island had power of language because their speaking arose in the interface of consciousness and the natural world. Connected.

SM

Can you talk about this in the context of work you're currently doing?

OO

The piece I’m writing and will begin rehearsing soon has a central character whose experience of God and direction in life, which she acts upon, doesn’t arise from education or a religious body and teaching. Her experience arises from Nature and perception of what stands behind its form, function, and beauty. Because she is in relationship with that she cannot be controlled by the system of her culture.

SM

You've taught extensively. What do you teach?

OO

Well, what you've got is a body, a voice, an imagination and your thoughts and feelings. You're going to speak, and your body is part of language. You’re going to speak, and speaking is voicing your self.

SM

I've seen you tell stories to an audience several times. The stories are evening-length and seem like a complex piece of music with many movements – yet they emanate from one slender woman sitting on a stool. I'm very moved by that. For me it’s related to the pure way one feels the range of a consummate vocalist singing a cappella. There’s a kind of fluid attention of the audience that has something to do with the magnificence of the song and the intimacy of the singer.

What’s it like to tell those stories?

OO

The hardest part of telling stories for me was eye contact with the audience, which you don't get in a blackout theatre. It is also the gift because in the moment ofconnecting through eyes you have relationship. You speak into a relationship which means the story is created by the audience more than other performance forms I have done. You speak into the privilege that the listener allows you to see them. The pool of the story is beholding each other before words or gestures are there. Or not in a performance setting, the pool is a crackling fire which teller and listeners look into and imagine together from.

SM

Did you grow into it?

OO

Yes and it did take time. I was in a really big hall in Yorkshire, with masses of rows of people, out there on my chair, and the story (an Alan Bennett piece) had started. I decided I would avoid eyes until I got settled and when I did finally take courage in hand, I picked a seat in the middle of the back row. And found the eyes of a dog! A big dog. He was sitting there on his haunches in his own chair. He was really paying attention because when you're performing you have focused energy and animals feel that. It took everything I had to hold myself together in rising hysteria. Laughing. Seriously … you have to hold the space for the story from a deep anchor in your self. Big ships, big stories, need big anchors and small ships, a little boat of a story has a small anchor. Without anchor, being unprotected by blackout, the dog and distractions, you can be thrown into this mid-space. There, stories get shallow, posturing, gloss, habits start running the show.

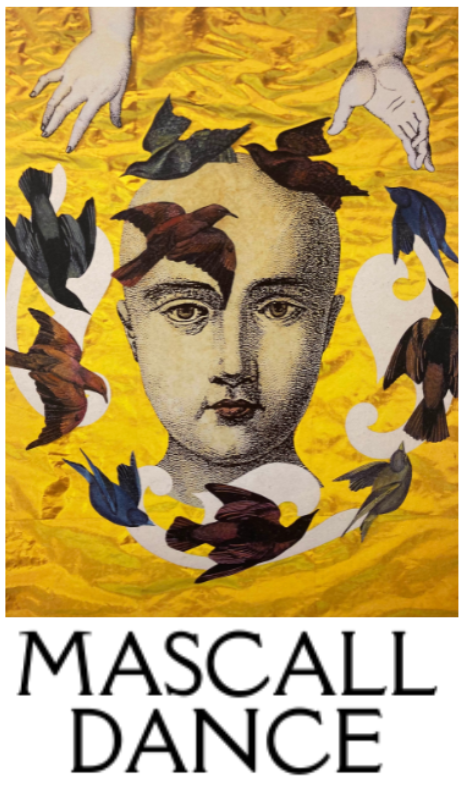

PARZIVAL retold Olivia Olsen